Filling a Weak Spot in Women’s Tennis: The Serve

“The men you’ll see, they’ll do things technically wrong, but because they’re so strong they’ll get away with it,” said Michael Joyce, who has coached several WTA players. “A lot of it is just because of brute strength.”

Joyce, who currently coaches Victoria Azarenka, has worked with younger players, and he said a pivotal divergence between boys’ and girls’ serving may happen in puberty, when boys are eager to show off their growing strength by blasting powerful serves in a way that girls cannot.

“Once the boys start to hit puberty and get stronger, all the sudden it’s like a macho thing: I’m going to step to the line and serve big and come to the net,” he said. “The mentality is just different.”

Because teenage girls do not have that same ability, Joyce said, they focus on other areas of their development instead. Boys quickly learn that having a robust serve is a necessity.

“Women don’t necessarily win with their serve, even in the juniors,” he said. “So it doesn’t become a huge priority. When I look back at when I was 14, 15 and started to play against older men, I knew I had to hold my serve.”

With shaky serves, many top women’s players have instead dominated with opportunistic returning. Angelique Kerber, who won the Australian Open and the United States Open last year, rarely won free points on her serve even as she rose to the No. 1 ranking last year.

Roger Federer, who played mixed doubles for the first time in 15 years at Hopman Cup in January, said that the women he faced did not disguise the direction of their serves as well as most male opponents, but he marveled at the exceptional returning acumen of his partner, Belinda Bencic.

“I think that first coach that teaches you the serve is superimportant — maybe emphasis in the women’s game is not the No. 1,” Federer said. “They spend much more time returning. I feel, that we don’t do at all. I don’t, anyway. I don’t practice my return at all.”

Building a Game Around Aces

The tracks that diverge in teenage players usually stay separate, unless a player or coach decides to make the serve a point of special attention.

When the Australian coach David Taylor began working with Naomi Osaka, a young Japanese player with a powerful serve, he said he made his focus on her serve unmistakable.

“I said right from the start that we have to build a game plan around holding serve,” he said. “I think that this is the way, that you have a game around holding serve, not around breaking. The more coaches that do this, and the more players that are able to do this, it will happen.”

Christopher Kas, a former doubles specialist on the ATP Tour, has coached WTA players in his post-playing career, first working with Sabine Lisicki and now with Mona Barthel.

When he began to work with WTA players, Kas did as much research as he could on the differences between men’s and women’s tennis, watching YouTube videos contrasting techniques between the tours and consulting with doctors on the physical differences between male and female athletes. While he understands the differences in musculature, Kas prioritizes serving, which was an existing strength for Lisicki and Barthel.

The 6-foot-1 Barthel, 27, has had a resurgence this year with an increased emphasis on her serve, and her ranking climbed from 183rd to the top 50 (she is now ranked 51st).

“With Mona, we try to use it as a weapon, and we try to gain confidence on return through good service games,” Kas said. “There might be other girls where it’s the other way around. They try to return well, and then protect the serve.”

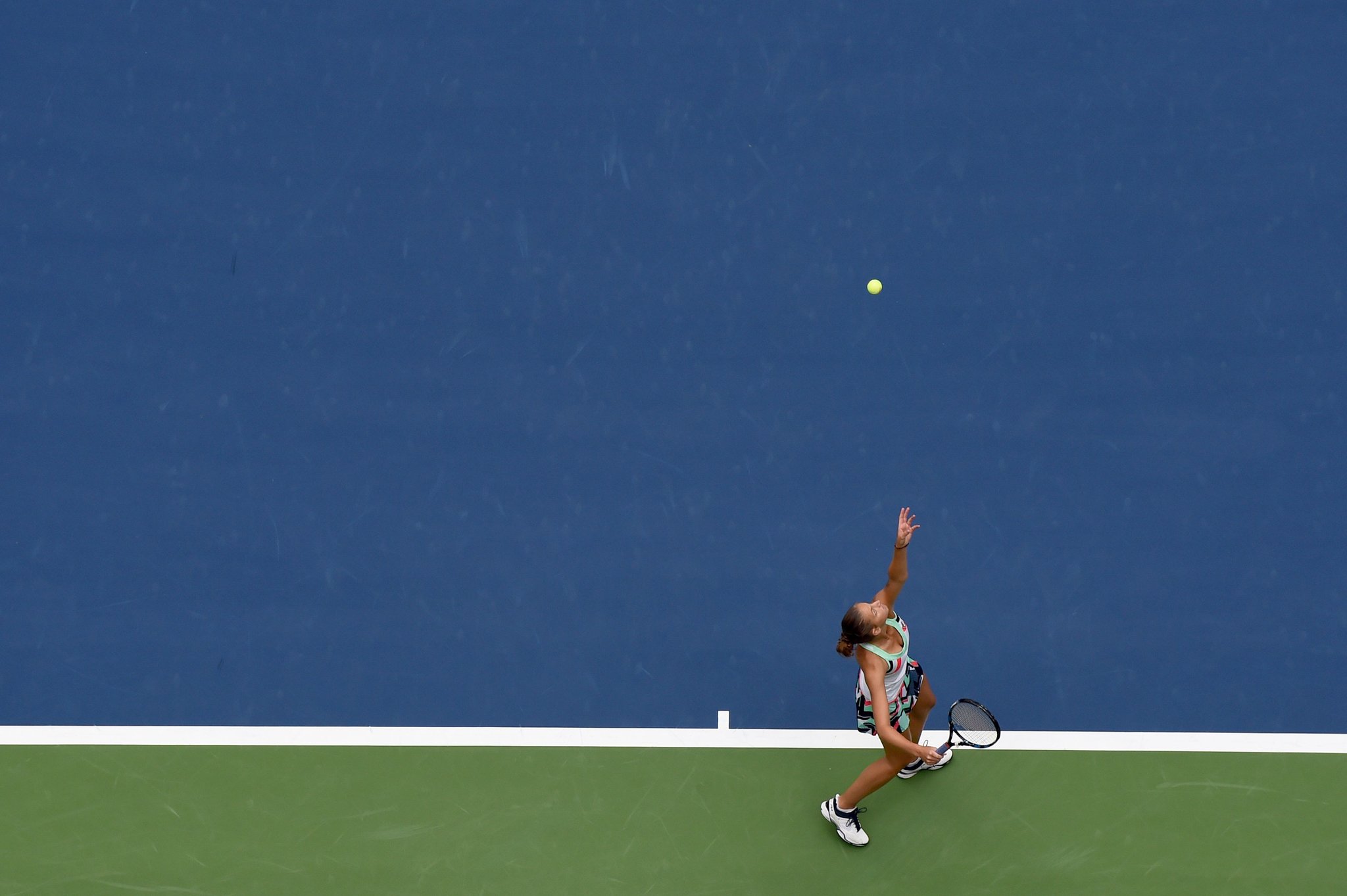

Credit

Jewel Samad/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

While height is not a requirement for great serving, it certainly is an advantage.

Top-ranked Karolina Pliskova is 6-foot-1 and led the WTA in aces each of the last two seasons.

“It’s always fun if you hit an ace and you don’t have to run anywhere,” she said. “It’s just a big advantage to have a serve like this, and a big help. Especially on days when I don’t hit well from the baseline, I can still play, somehow, and get some points from the serve, which is really important. You don’t always have to go through the rally, and you have some easy points.”

Naomi Broady, a 6-foot-2 player who struggles to match the agility of her peers, said she had always known her serve was her best shot, but only recently had thought it possible to model her game after dominant male servers like Ivo Karlovic and John Isner.

“Coming into the higher level of tennis, the girls are much better than I am off the ground,” said Broady, 27, who is ranked 125th. They’re much more compact. They’re better movers than I am, and technically more solid, so I had to be really smart about my game, and see how I could compete with these girls who play better than me from the baseline. The simple option was to separate the games between service games and return games.”

The transformation has paid off with a late-career surge: Broady broke into the top 100 for the first time last year, just weeks before her 26th birthday. She cited Karlovic’s ability to still win ATP titles in his late 30s, as evidence that big servers can be disrupters of conventional tennis wisdom.

Mouratoglou, Williams’s coach, said more women and their coaches were recognizing that a serve-focused game could be a viable strategy in the WTA.

“It’s cultural, because if you don’t make the player feel that it’s important that she’s able to ace, and then if you don’t work on it, it’s not going to happen,” Mouratoglou said. “I think it’s changing now: They’re serving better and better. And when you start to see quite a few girls serving well, the others will say, ‘Oh, we can serve well. We can hit aces.’ It’s much more in the culture now.”

Continue reading the main story